In theory, anything computational is a function - including numbers. In this article, we'll explore how to represent numbers and carry out some basic arithmetic operations using nothing but functions.

1. Breaking Down Numbers.

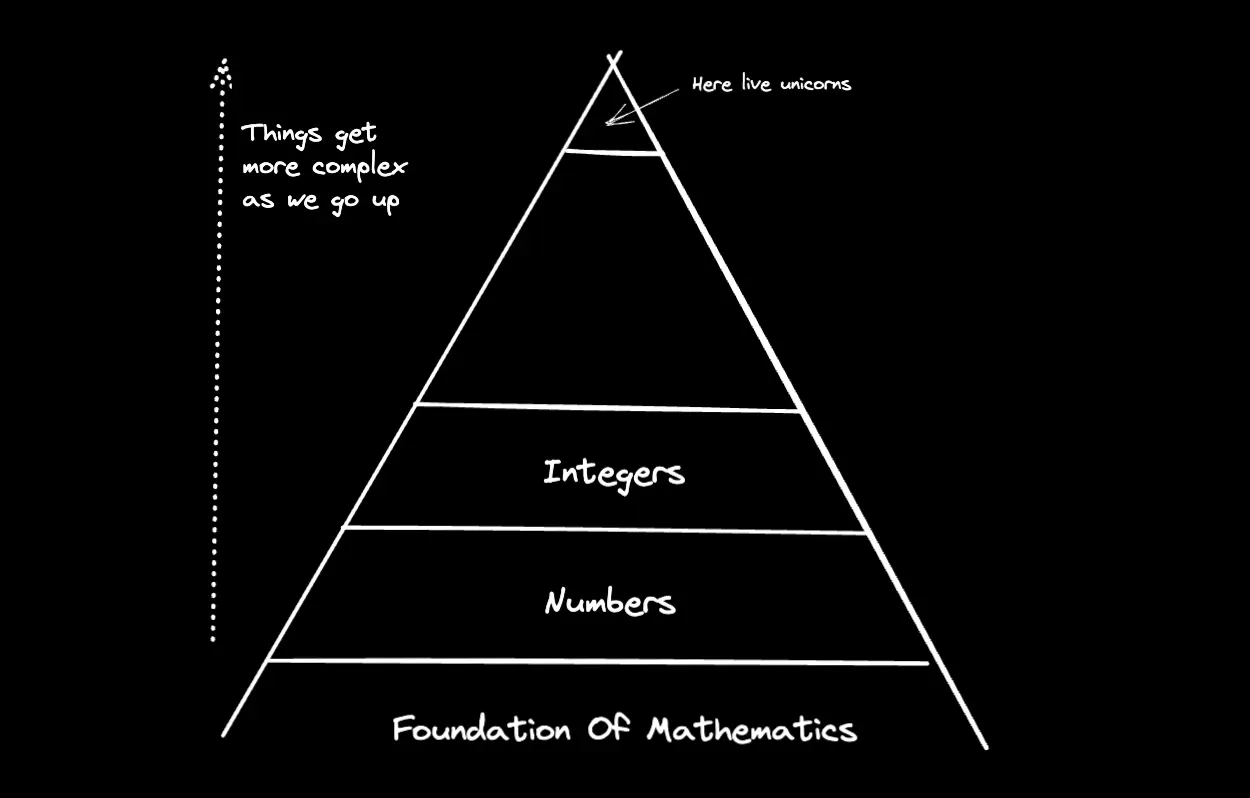

A basic, but crucial, idea in mathematics is that complex things are built on top of simpler things. In other words, complex mathematical structures are derivable from simpler ones. So, for any reasonably complex mathematical structure, we can break it down into its simpler substructures. For example, the real numbers are built on top of the rational numbers. In turn, these are derived from the integers which can be broken down into the natural numbers.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, mathematicians and philosophers alike pondered on our basic and crucial idea. In particular, they pondered on the extent to which we can break down all mathematical structures. Crucially, they were in search of a foundation for all of mathematics. They pondered on whether there was any such thing as the simplest mathematical structure - a sort of mathematical atom. These atoms would be the foundations upon which all other mathematical structures are built. They thought that, with this foundation in hand, we would be able to mechanically/programatically derive any mathematical structure irrespective of its complexity. As a result, all mathematical structures would be broken down into these atoms. In other words, we can picture mathematics itself as a pyramid of structures stacked on top of each other. Complex mathematical structures are on top while the 'simpler' structures are nearer to the foundation.

Naturally, in their search of the mathematical atoms, they pondered on numbers and how to break them down into simpler substructures. In particular, thanks to the work of Giuseppe Peano, we were able to derive numbers from a simpler structure called the Peano Axioms. These are as follows:

- Zero is a number.

- The successor of a number is a number.

- If the successors of two numbers are equal, then they are the same number.

- Zero is not the successor of any number.

- Equality '=' is reflexive, symmetric, transitive and closed.

For our current purposes, we do not need to understand the technical details and terms behind these axioms. The only idea to keep in mind is that numbers are built on top of simpler structures. Particularly, we can derive them from the "simpler" Peano axioms. More importantly, we can break down numbers into simpler things.

2. Numbers As Functions.

Since we can break down numbers into simpler things, this intuitively means that numbers do not have to be just numbers. They are mere fictions which can be represented by simpler things. In particular, numbers can be represented by functions! To clarify, we say that a function is a blackbox that takes an input and returns an output. Then, we follow Alonzo Church in proposing that a number represents the amount of times that an arbitrary function is called. So, a number N calls that function N times.

In essence, a number N is a function that calls another arbitrary function N times.

So, the number 0 is a function that calls some other function zero times. In particular, it takes an arbitrary function F and a value V as inputs. Then, it only returns that value without calling the function. It completely ignores the function F.

0 = F => V => V

In the same line of thought, the number 1 is a function that calls some other function one time. In particular, it takes an arbitrary function F and a value V as inputs. Then, it returns that function with the value as its argument.

1 = F => V => F(V)

Naturally, the number 2 is a function that calls some other function two times. In particular, it takes an arbitrary function F and a value V as inputs. Then, it returns the function with the value as its argument within the function itself.

2 = F => V => F(F(V))

Finally, we can recursively define other numbers as follows:

3 = F => V => F(F(F(V)))

4 = F => V => F(F(F(F(V))))

...

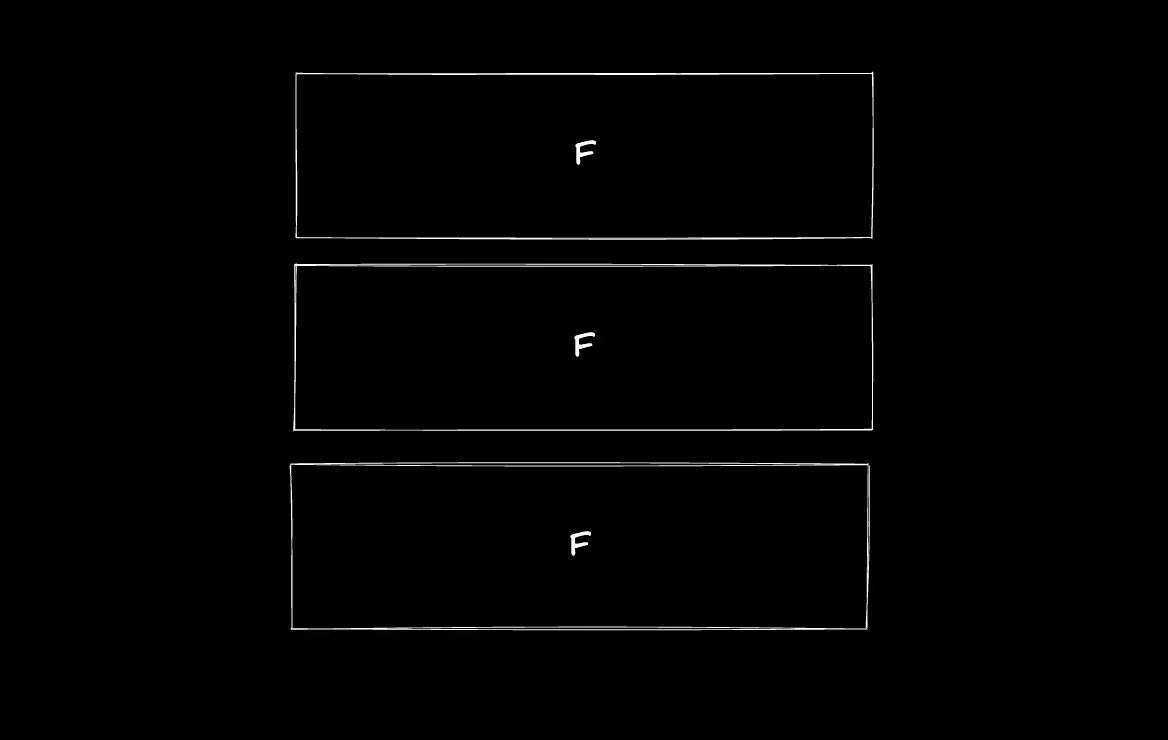

Intuitively, we may also visualise a number as the amount of times that our arbitrary function is added to a stack. So, the number 3 would call the function F thrice and add it to the stack thrice.

In particular, since 3 is F(F(F(V))), it adds F to the stack and returns F(F(V)). The latter calls F a second time, adds it to the stack and returns F(V). Finally, F is called and added to the stack for a total of 3 times.

3. Numbers As JS Functions.

In JavaScript, we may now define the first four numbers as follows:

const zero = F => V => V;

const one = F => V => F(V);

const two = F => V => F(F(V));

const three = F => V => F(F(F(V)));

In order to test our definitions, we define our arbitrary function as trackerFunc and a variable trackerFuncCallCount that counts the amount of times that trackerFunc is called.

let trackerFuncCallCount = 0;

const trackerFunc = () => {

trackerFuncCallCount++; // increments for each function call

}

To test the definition of zero, we call it with trackerFunc as the arbitrary function and log the value of trackerFuncCallCount. We see that trackerFuncCallCount remains 0.

zero(trackerFunc)();

console.log(trackerFuncCallCount); // => 0

Additionally, to test the definition of one, we call it with trackerFunc as the arbitrary function and log the value of trackerFuncCallCount. We see that trackerFuncCallCount is 1!

one(trackerFunc)();

console.log(trackerFuncCallCount); // => 1

Moreover, we also see that the function two calls trackerFunc twice and three calls trackerFunc thrice!

two(trackerFunc)(); // trackerFuncCallCount => 2

three(trackerFunc)(); // trackerFuncCallCount => 3

In sum, we can track the amount of times that a number calls the function trackerFunc in the following table:

| Number | # of trackerFunc calls |

|---|---|

[Function: zero] | 0 |

[Function: one] | 1 |

[Function: two] | 2 |

[Function: three] | 3 |

From our table, we can easily see that any number N is a function that calls another arbitrary function N times. So, we've broken down numbers into simpler things. In particular, we've seen how numbers can be built on top of simple blackboxes that takes an input and returns an output. Hence, numbers can be represented by nothing but functions!

4. Basic Arithmetic Operations As Functions.

So far, we can't do much with these numbers as functions yet. We wanna be able to carry out some basic arithmetic operations with them as well. For our current scope, we only look at how to represent addition and multiplication as functions. If you're curious about the rest, check out the notes at the end of this article.

4.1 Addition.

Following Alonzo Church, let's propose that adding two numbers N and M together is like calling an arbitrary function N times and then calling it again M times. So, addition is a function that takes two numbers-as-functions N and M, an arbitrary function F and a value V and returns the function N that calls F for an N amount of times times with M(F)(V) as its value. In turn, M(F)(V) is the function M that calls F for an M amount of times with V as its value.

"+" = N => M => F => V => N(F)(M(F)(V))

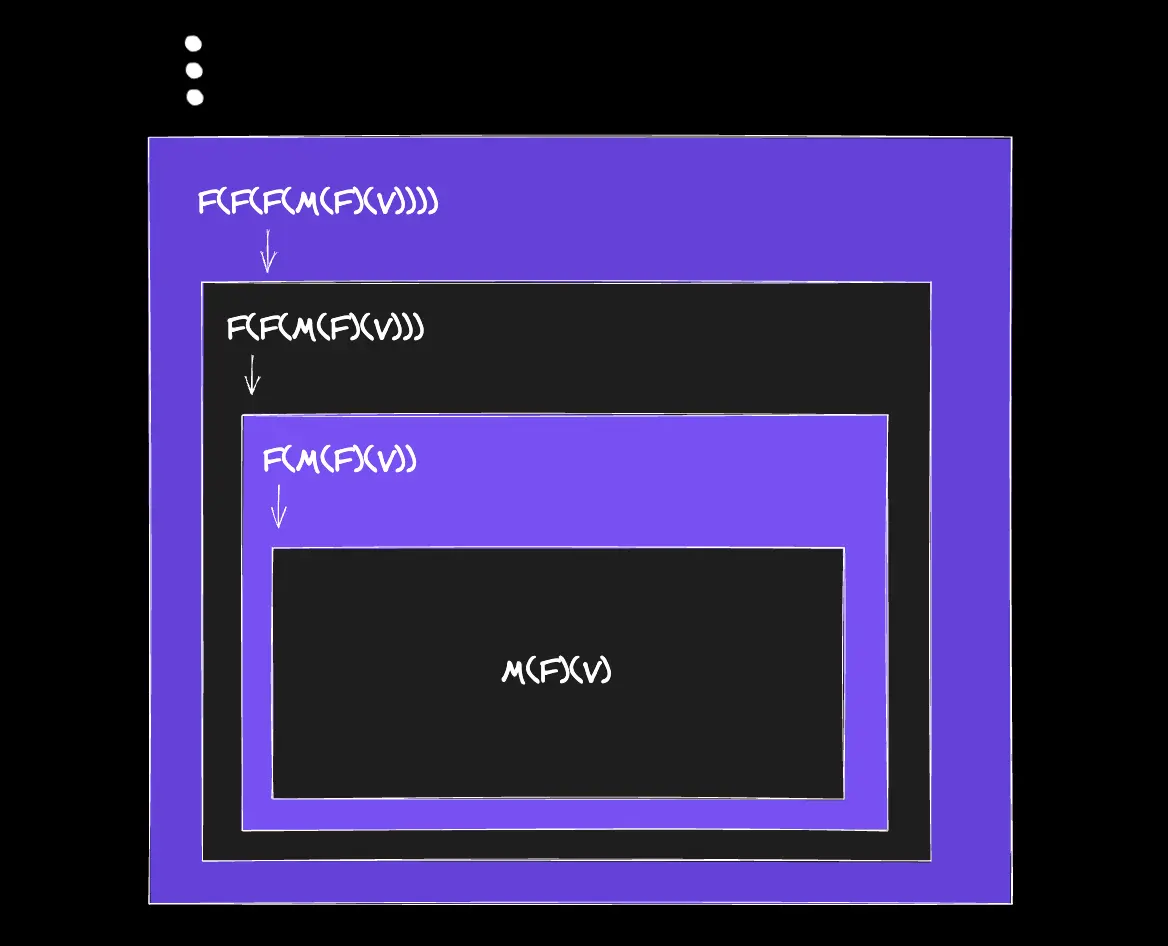

Let's clarify the return of our addition function - N(F)(M(F)(V)). Let's not forget that N and M represent numbers as functions. Remember that a number N is a function that calls an arbitrary function F for an N amount of times.

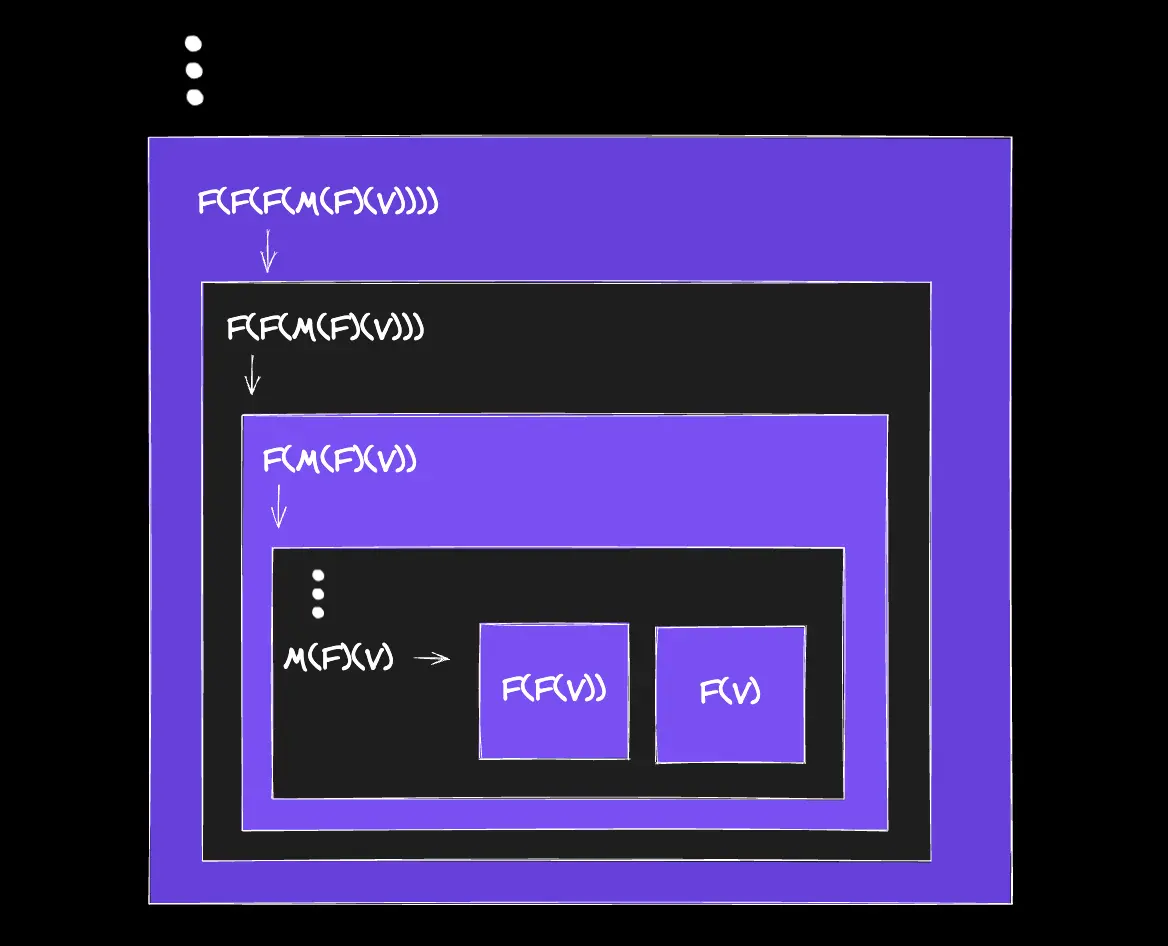

So, N(F)(M(F)(V)) is simply passing the function F and M(F)(V) as arguments to the number-as-function N. So, N will call F N times with M(F)(V) as the value of F. Importantly, remember that F is called with the value M(F)(V) only on the last call of F. In other words, N(F)(M(F)(V)) evaluates to something like ...F(F(F(M(F)(V)))). Visually:

Now, M(F)(V) remains after F is called N times. To evaluate M(F)(V), remember that a number M is a function that calls an arbitrary function F for an M amount of times. So, M(F)(V) is simply passing the function F and V as arguments to the number-as-function M. So, M will call F M times with V as the value of F. Importantly, remember that F is called with the value V only on the last call of F. In other words, M(F)(V) evaluates to something like ...F(F(V)). Visually:

Hence, we can see how our addition function calls an arbitrary function for a total of (N + M) times.

4.2 Multiplication.

For multiplication, let's propose that multiplying two numbers N and M together is like calling an arbitrary function N times. Then, for each time that it is called during these N times, we call it for an M amount of times. So, multiplication is a function that takes two numbers-as-functions N and M, an arbitrary function F and a value V and returns the function N that calls M for an N amount of times times with the value V. In particular, M is called with the function F as argument. In turn, for each time that M is called during these N times, M calls the function F for an M amount of times with V as its value.

"*" = N => M => F => V => N(M(F))(V)

Let's clarify the return of our multiplication function - N(M(F))(V). Let's not forget that N and M represent numbers as functions. Remember that a number N is a function that calls an arbitrary function F for an N amount of times.

So, N(M(F))(V) is simply passing the function M(F) and V as arguments to the number-as-function N. So, N will call M(F) N times. Visually:

Now, for each time that N calls M(F), we call F for an M amount of times. Visually:

Intuitively, we have a multiplication table made up of N columns and M rows. Hence, we can see how our multiplication function calls an arbitrary function for a total of (N * M) times.

5. Basic Arithmetic Operations As JS Functions.

In JavaScript, we may now define addition and multiplication as follows:

const add = N => M => F => V => N(F)(M(F)(V));

const multiply = N => M => F => V => N(M(F))(V);

As we previously did, we use trackerFunc and the variable trackerFuncCallCount to count the number of times that trackerFunc is called.

5.1 Addition.

To test the definition of add, firstly, we call it with one, two and trackerFunc as arguments. Secondly, we also try three, three and trackerFunc as arguments.

// 1 + 2

add(one)(two)(trackerFunc)(); // trackerFuncCallCount => 3

// 3 + 3

add(three)(three)(trackerFunc)(); // trackerFuncCallCount => 6

Amazingly enough, we see that trackerFuncCallCount is 3 for one and two. This means that, as expected, trackerFunc has been called thrice.

We also see that trackerFuncCallCount is 6 for three and three. This means that, as expected, trackerFunc has been called 6 times.

Hence, we can easily see that addition of two numbers N and M is simply calling an arbitrary function N times and then M times.

5.2 Multiplication.

To test the definition of multiply, firstly, we call it with one, two and trackerFunc as arguments. Secondly, we also try three, three and trackerFunc as arguments.

// 1 * 2

multiply(one)(two)(trackerFunc)(); // trackerFuncCallCount => 2

// 3 * 3

multiply(three)(three)(trackerFunc)(); // trackerFuncCallCount => 9

Amazingly enough, we see that trackerFuncCallCount is 2 for one and two. This means that, as expected, trackerFunc has been called twice.

We also see that trackerFuncCallCount is 9 for three and three. This means that, as expected, trackerFunc has been called 9 times.

Hence, we can easily see that multiplication of two numbers N and M is simply calling an arbitrary function N times and for each call, we call that function M times.

Finally, we can track the number of times that an arithmetic operation calls trackerFunc in the following table:

| Operation | # of trackerFunc calls |

|---|---|

| 1 + 2 | 3 |

| 3 + 3 | 6 |

| 1 * 2 | 2 |

| 3 * 3 | 9 |

From our table, we can easily see that, firstly, addition of two numbers N and M is simply calling an arbitrary function N times and then M times. Secondly, multiplication of two numbers N and M is simply calling an arbitrary function N times and for each call, we call that function M times.

So, we've broken down some basic arithmetic operation into simpler things. In particular, we've seen how arithmetic can be built on top of simple blackboxes that takes an input and returns an output. Hence, basic arithmetic operations can be carried out using nothing but functions!

In sum, we saw that numbers can be broken down into the simple Peano Axioms. This invited the possibility that numbers are mere fictions which can be represented by functions. Finally, following Alonzo Church, we represented numbers and carried out some basic arithmetic operations, like addition and multiplication, using nothing but functions.

PS.

A. It turns out that we cannot derive all mathematical structures. This is because of Gödel's Incompleteness Theorems. This implies that, firstly, there are true mathematical statements that cannot be proven. Secondly, it also implies that we cannot prove that mathematics is consistent. In other words, we cannot prove that mathematics itself does not lead to a contradiction.

B. If you want to dive deeper into the Peano Axioms. I highly recommend Bertrand Russell's Introduction To Mathematical Philosophy. Interestingly, we can also prove that all Peano Axioms are derivable from Hume's Principle in Second-Order Logic. This is called Frege's Theorem. Check out my proof here.

C. We can go even further and derive numbers from just sets. In particular, we define 0 as the empty set "∅" and recursively define numbers as follows:

0 = ∅

1 = {∅}

2 = {∅, {∅}}

3 = {∅, {∅}, {∅, {∅}}}

...

D. Representing a number N as a function that calls another arbitrary function N times is commonly known as the Church Numerals.

E. We can represent other arithmetic operations such as subtraction and division using Church Encodings. Find out more here. For example, we can do exponentiation as follows:

"^" = N => M => F => V => (M(N))(F)(V)

F. Notice that the Peano Axioms has a "successor" predicate. We can also represent this as a function as follows:

"successor" = N => F => V => F(N(F)(V))

We can also represent the predecessor of a number as follows:

"predecessor" = N => F => V => N(g => h => h(g(F)))(u => V)(u => u)

G. Notice that the Peano Axioms also talks of equality "=". We can also represent identity as a function as follows:

"=" = V => V

It's interesting to see that V => V is also reflexive, symmetric, transitive and closed.

H. The philosophical interest of representing numbers as functions is ontological abstraction and its implication about the nature of computation. In other words, we see that functions are ontologically prior to numbers and arithmetic. Moreover, despite the heavy use of numbers in computer programs, we see that we could (in principle) re-write all programs without any explicit reference to numbers themselves. This is exactly what happens in the Lambda Calculus. So, in a way, we could say that numbers are not in the essence of computation itself.

I. Here's all the code that we've seen (and more) in one place (Reload the page if you can't see the code or see the gist here).

J. I may have, unintentionally, left some technical or mathematical errors in this article. If you spot them, kindly send a PR to this repo or send me an email - houzairmk@icloud.com.