Here’s an interesting fact — even if we had an infinite amount of computational power and time, we would not be able to solve every single computational problem that can exist. In this article, we’ll informally prove this fact by showing that there are far too many problems for programs to handle.

1. The Road Ahead.

Essentially, we have to show that the number of problems is greater than the number of programs available to solve them. Naturally, we need a way to count these programs and problems. So, we’ll count these by comparing the sets of all programs and problems to the sets of natural and real numbers respectively. In particular, we’ll establish the following statements.

a. The size of the set of computational programs is less or equal to the size of the set of natural numbers.

b. The size of the set of computational problems is equal to the size of the set of real numbers.

Subsequently, we’ll visually prove that, even if the set of natural numbers is infinitely big, the set of real numbers is even bigger. In fact, the natural numbers are countably infinite but the real numbers are uncountably infinite. Consequently, we’ll establish the following statement.

c. The size of the set of natural numbers is less than the size of the set of real numbers.

Finally, with the help of our established statements (a, b and c), we’ll show that there are far too many problems for programs to handle.

2. How To Count Programs For Dummies.

JavaScript is a Turing complete language. This means that any program that a Turing machine can compute can be written in JavaScript. Alternatively, any program that can be written in JavaScript can be computed by a Turing machine. So, it is theoretically fair to assume that the set of all JavaScript programs corresponds to the set of all possible programs.

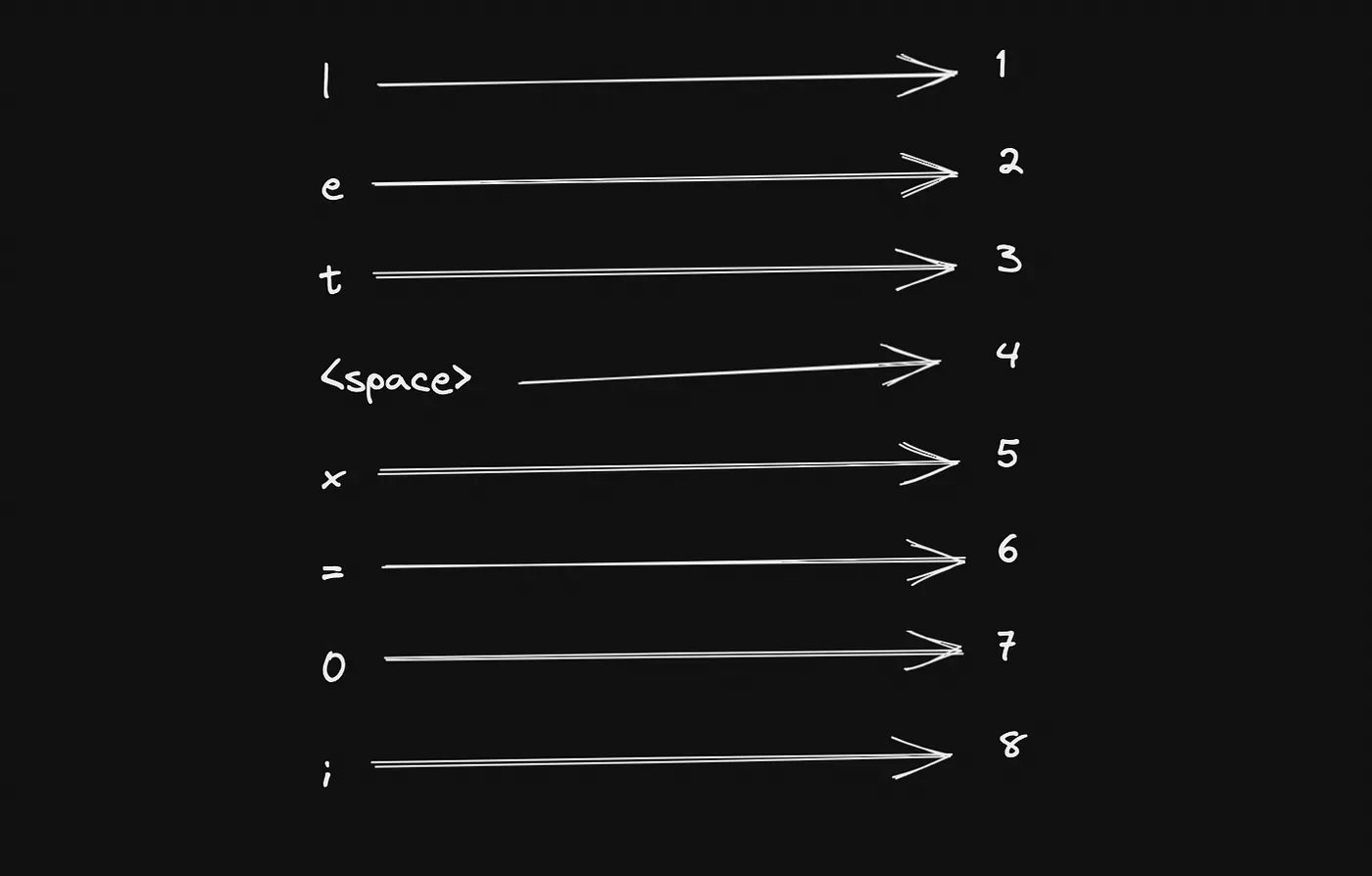

In order to count these programs, let’s assign a unique natural number to every possible character in the JavaScript syntax. For example, let’s say that the letter l maps to the number 1, e maps to 2 and t to 3. So, let maps to 123. Let’s even assign a unique number to the empty space.

With our mapping in hand, it’s easy to imagine how every possible sentence in JavaScript can be mapped to a unique number. Consequently, we can also map every single JavaScript program to a unique number. For example, let’s visualise our mapping as follows.

Intuitively, we can assign a program, like let x = 0;, to a unique number like 1234546478 . Since JavaScript is Turing complete and every JavaScript program can be mapped onto a unique natural number, we can deduce that the number of JavaScript programs is less or equal to the size of the set of natural numbers. So, we may establish our first statement.

a. The size of the set of computational programs is less or equal to the size of the set of natural numbers.

3. How To Count Problems For Dummies.

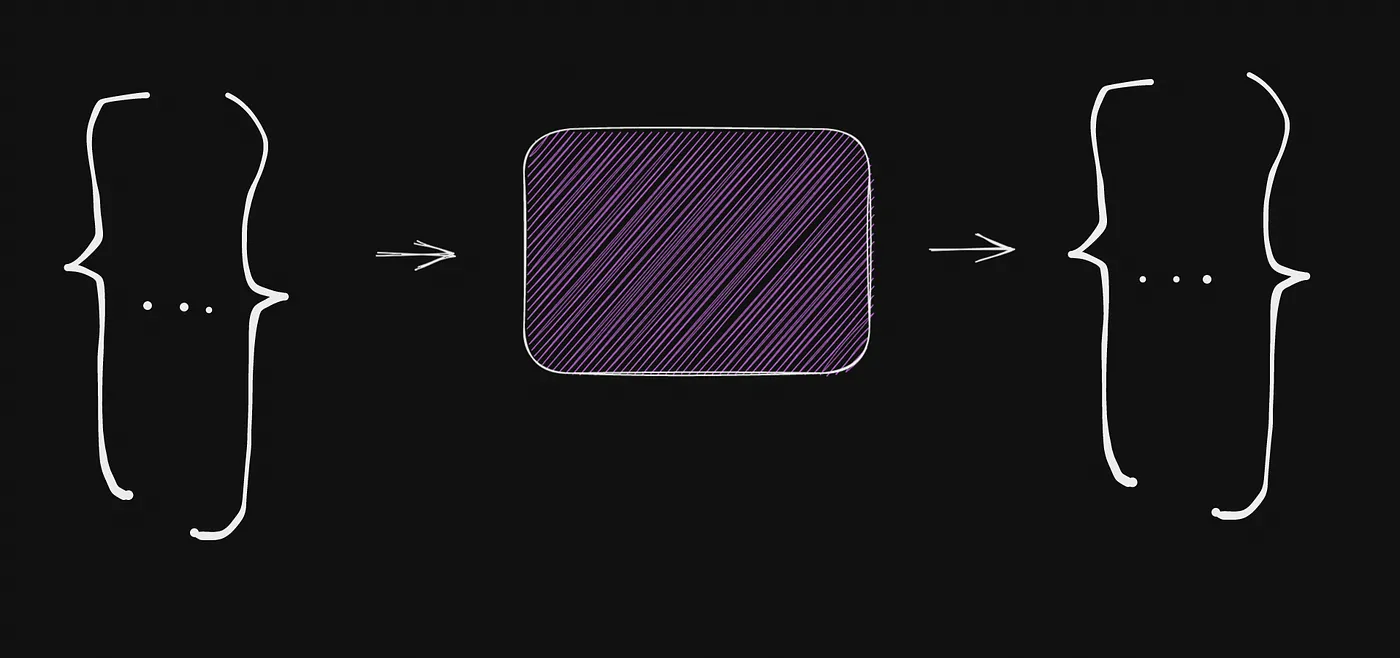

An intuitive way of picturing a computational problem is like a black-box that takes some input and has some associated desired output [1]. Then, to solve that problem is to find a program that gives the desired output based on the given input.

With this picture in mind, we can intuitively say that the set of inputs and the set of desired outputs could be any amount of strings of numbers. In other words, we can view a problem as a mathematical function that maps from the set of natural numbers to the set of natural numbers. So, to count the number of problems is to count the number of functions that maps from natural to natural numbers. Since we know that the size of the set of all such functions is equal to the size of the set of all real numbers, we may establish our second statement.

b. The size of the set of computational problems is equal to the size of the set of real numbers.

4. The Struggle Is Real.

Let’s visually establish that the there are more real than natural numbers by following a version of Cantor’s diagonal proof.

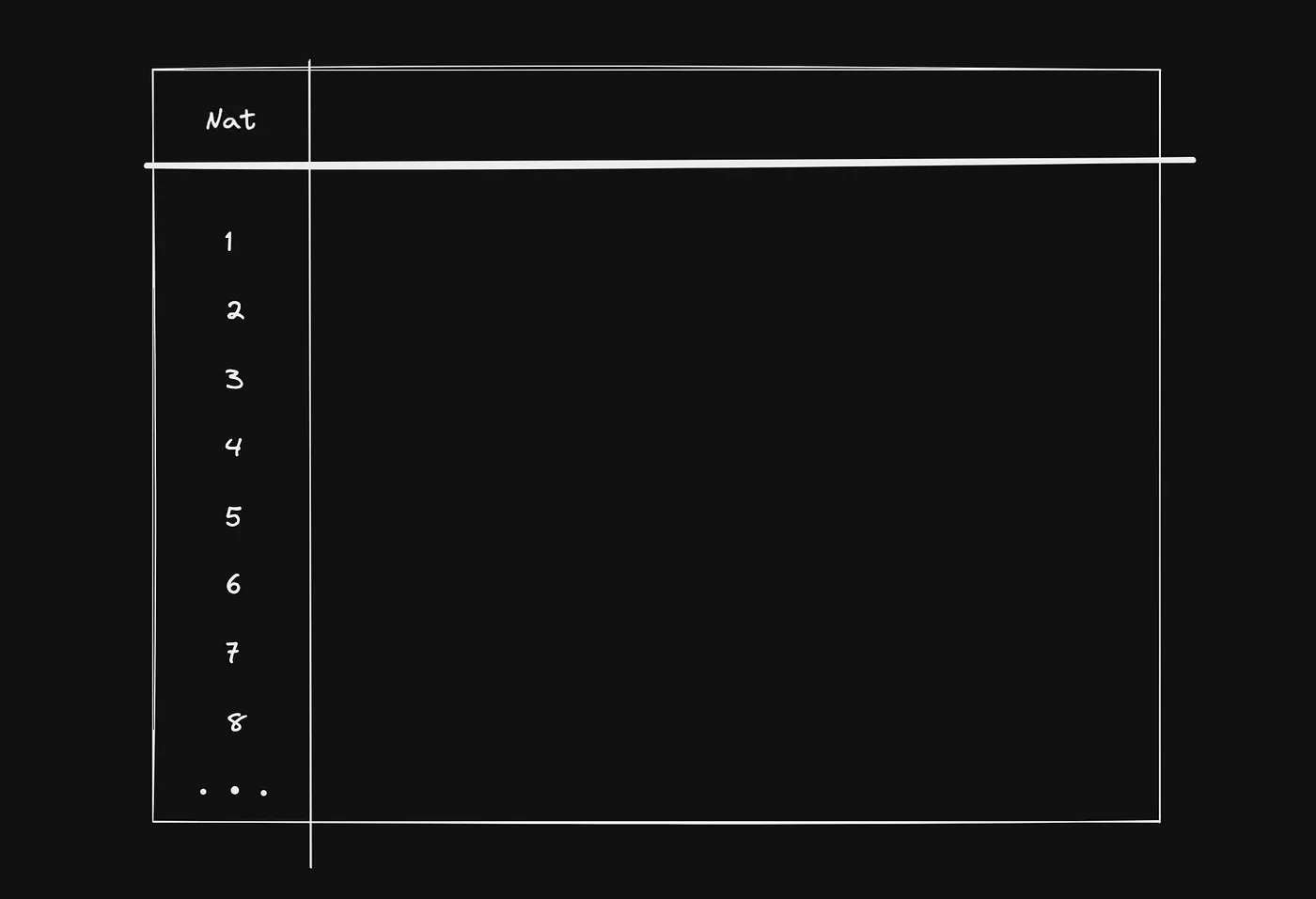

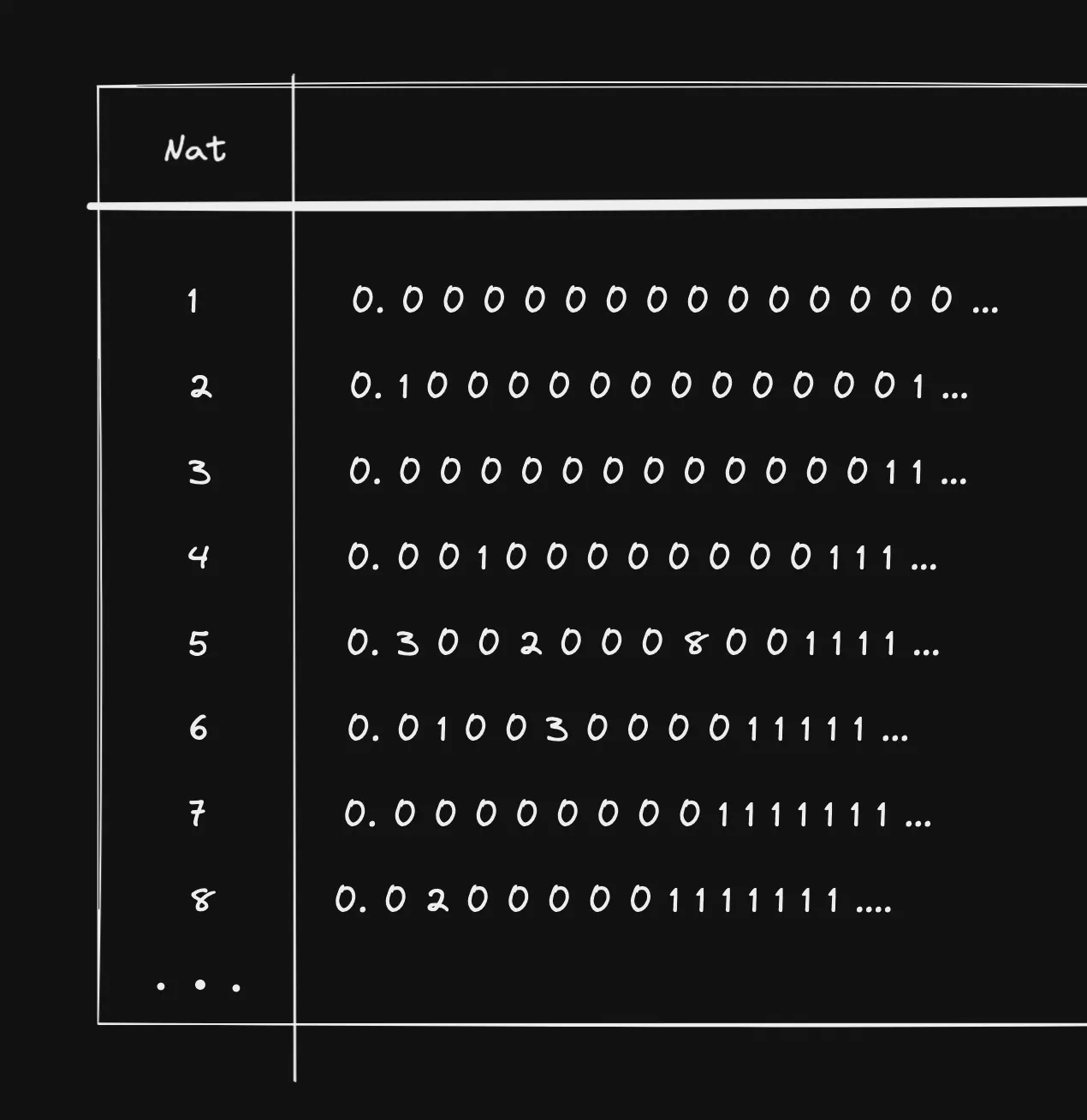

Intuitively, there are infinitely many natural numbers. So, let’s suppose that we’ve written all of them in an infinite table as follows.

In the second column, let’s try to write every real number such that we match a unique real number to every single natural number in our “Nat” column.

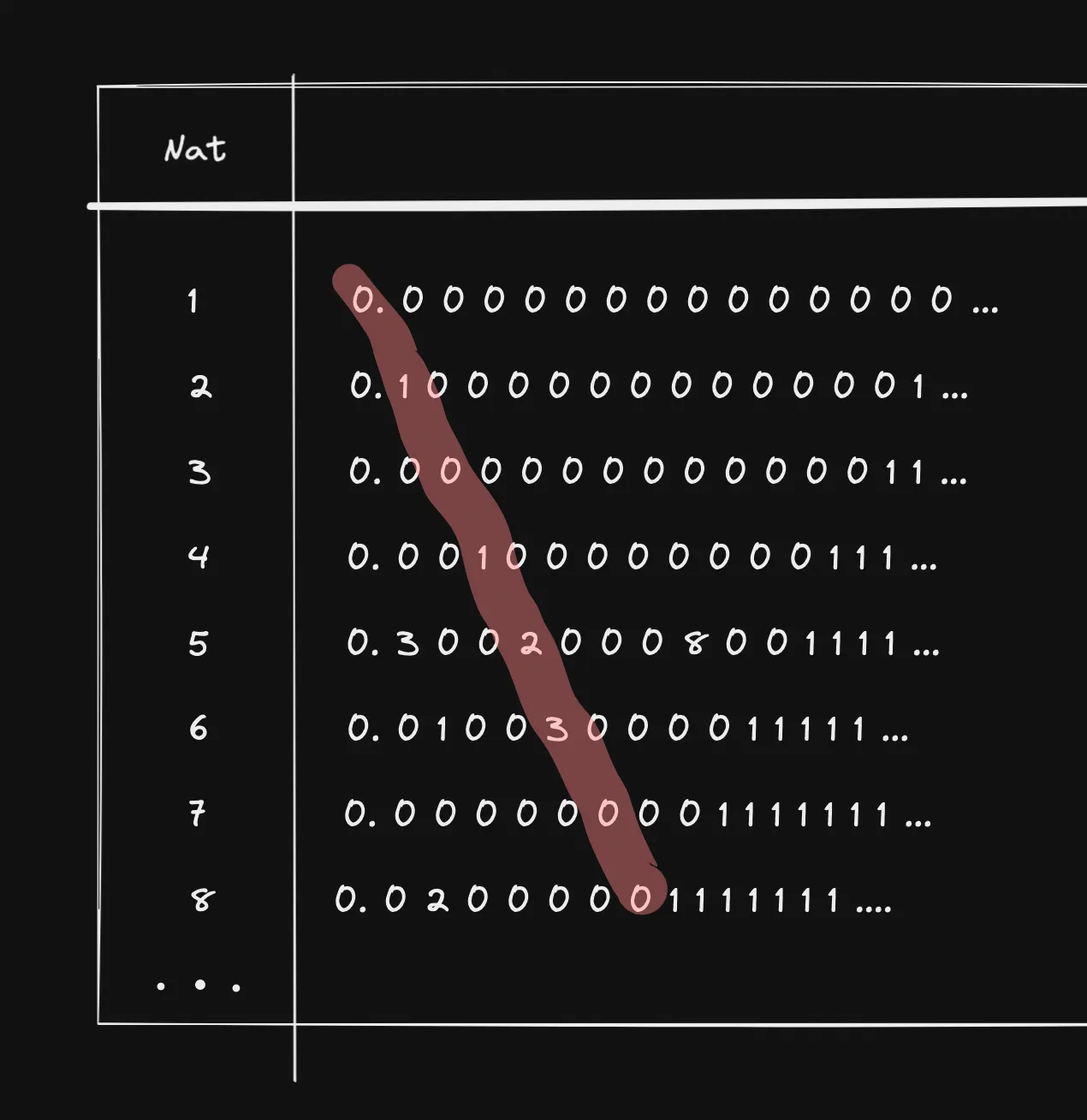

Subsequently, imagine a diagonal line that runs through each real number. Particularly, the line goes through the first digit in the first real number, the second digit in the second real number, and so on (ad infinitum).

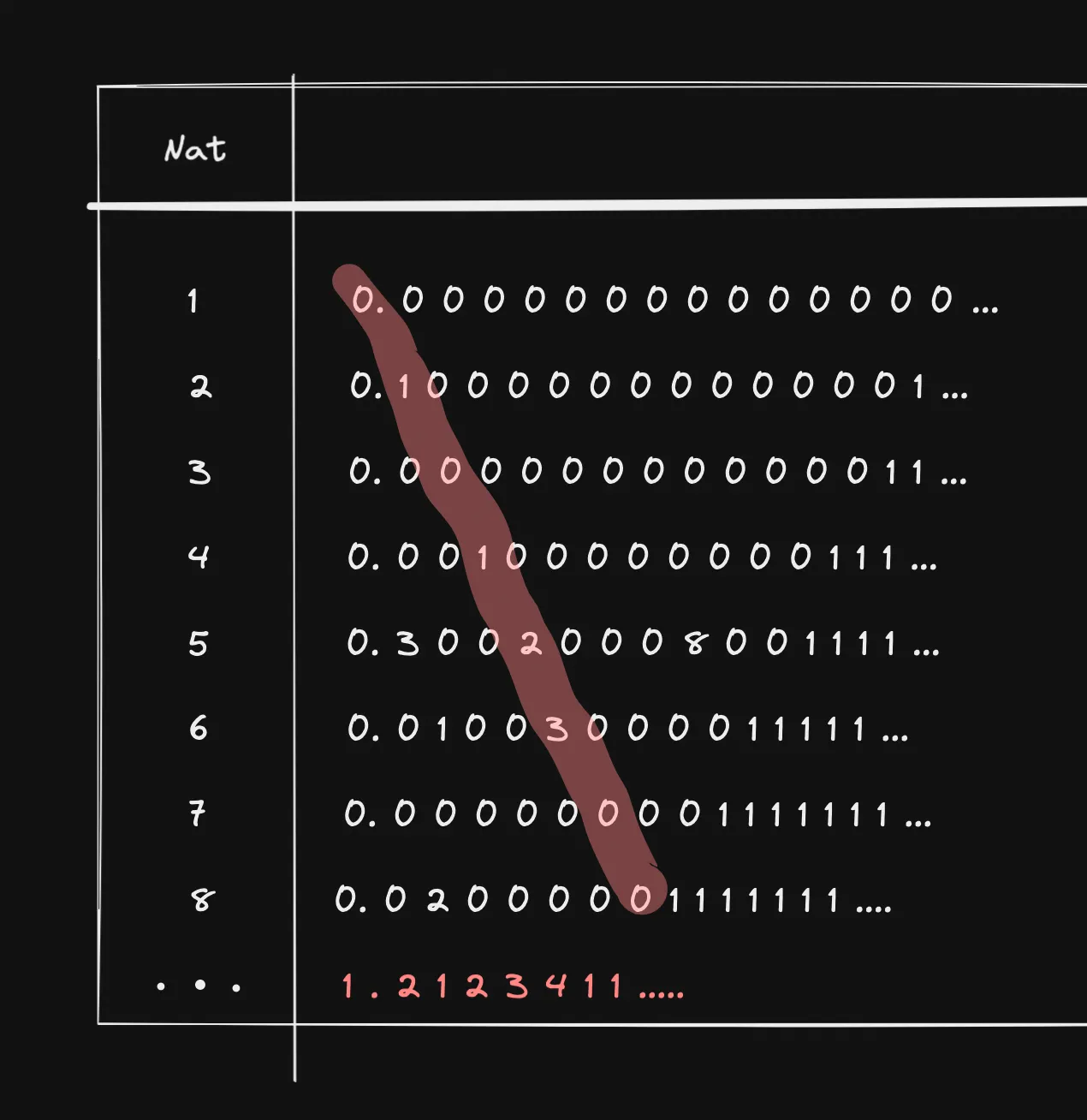

Finally, let’s apply a simple rule to our diagonal line — We will add 1 to every digit on our line. If it’s a 9, we will subtract 1. Once our rule is applied, we will generate a “new” real number and we may write it in the very last row of our infinite table.

Crucially, notice that this newly generated real number differs from every other real number in our infinite table. In particular, it differs from every other real number by at least one digit. Importantly, we can keep on generating such “new” real numbers by applying our rule over and over again.

Since our table is infinitely big, every newly generated real number will not be in this table. This shows that, even if there are infinitely many natural numbers, there are way more real numbers. In fact, this shows that there are infinities bigger than other infinities. However, for our current purposes, we may establish our last statement.

c. The size of the set of natural numbers is less than the size of the set of real numbers.

5. Wrapping Up.

So far, we’ve established the following three statements.

a. Size of the set of programs ≤ Size of the set of natural numbers.

b. Size of the set of problems = Size of the set of real numbers.

c. Size of the set of natural numbers < Size of the set of real numbers.

So, we can conclude the following:

Size of the set of programs < Size of the set of problems.

We are not out of the woods yet. Even if the number of programs is less than the number of problems, we cannot say that the number of problems is greater than the number of programs available to solve them. So, we shall also add that each program solves only one problem [2].

Consequently, if each program solves only one problem and there are less programs than problems, then the size of the set of solvable problems is less that the size of the set of all problems. Intuitively, this means that there are unsolvable problems. So, there are far too many problems for programs to handle.

In summary, we’ve counted the number of programs and problems. We’ve established that there are more problems than programs such that there are more problems than solvable problems. Hence, informally proving that, even if we had an infinite amount of computational power and time, we would not be able to solve every single computational problem.

PS.

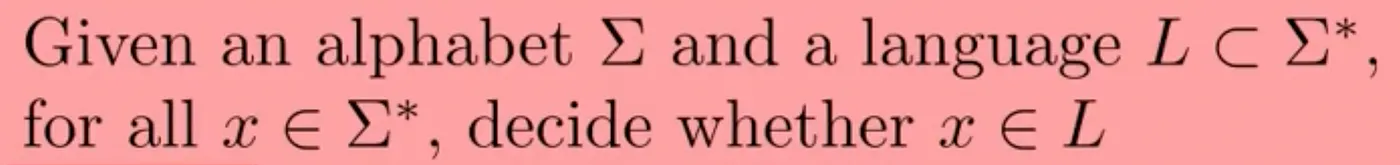

- Instead of picturing a computational problem like a black-box, we can formally define a problem as follows.

This defines every problem as a decision problem. However, for our current purposes, I believe that it’s more intuitive to see a problem as a black-box than purely as a decision problem.

- It is entirely plausible that two different programs solve the same problem. The important point is that we do not have a program that solves more than one problem.

Hey there, thanks for reading this far! If you spot any mathematical mistakes or essential steps that I’ve missed in my informal proof, please let me know — houzairmk@icloud.com.